Sinners: A Genre-Fluid Masterpiece that Reclaims Ancestral Roots Through Sound

Written By: Author Ishanae’ Pollard

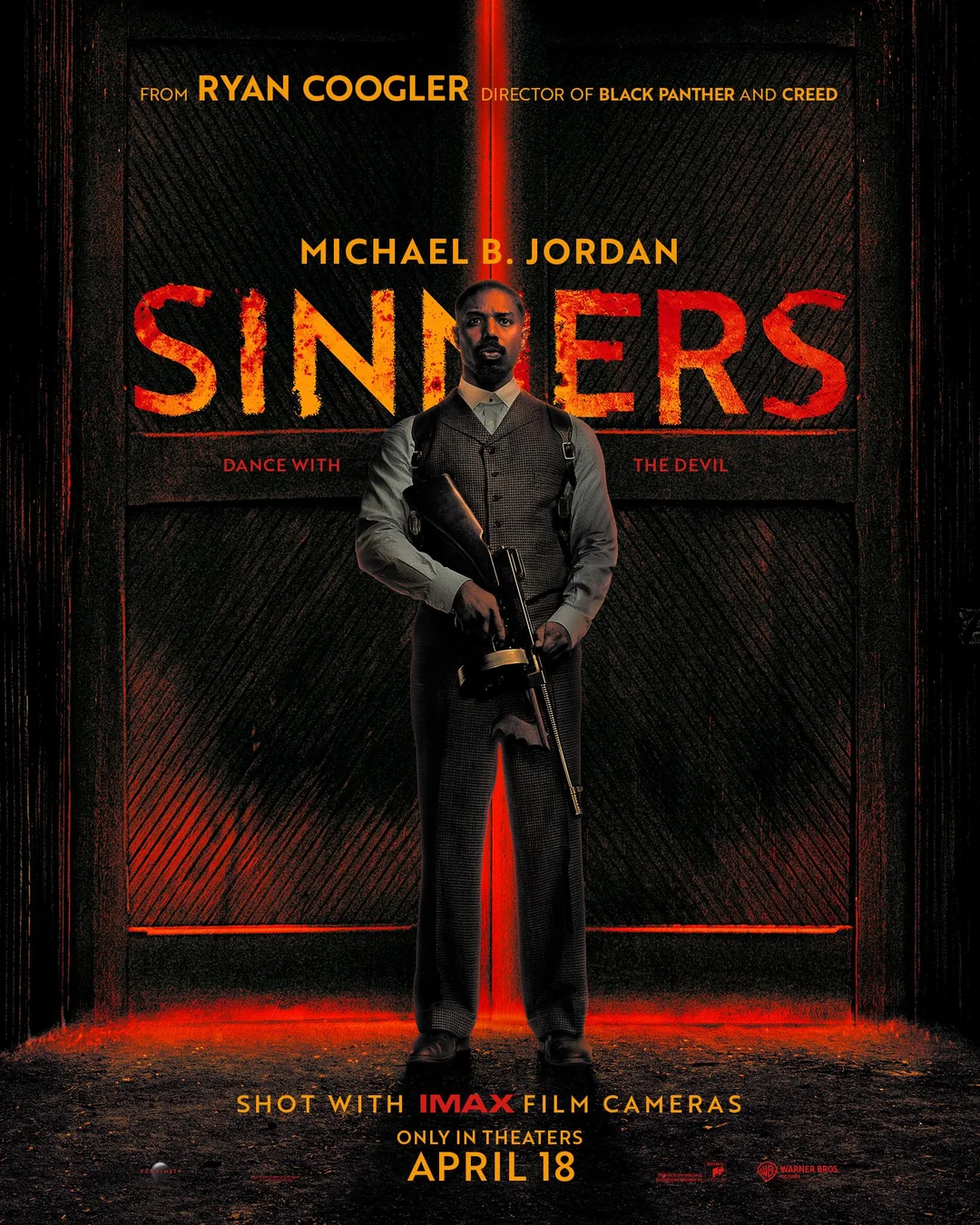

I watched Sinners for the second time today, and I can confidently say it’s not just a film—it’s an experience. Written, directed, and produced by the visionary Ryan Coogler and starring Michael B. Jordan, Sinners defies traditional genre boundaries. While it flirts with elements of horror, it transcends the label. This is not your typical vampire movie. This is a genre-fluid cinematic masterpiece rooted in history, culture, and the soul of Black music.

The story unfolds in Clarksdale, Mississippi, October 16, 1932, a time and place thick with trauma, legacy, and longing. Sinners is as much about spiritual warfare as it is about societal reckoning. At its core, the film is about music—how it heals, how it haunts, and how it holds the power to resurrect more than just memories.

The film centers around Sammie, a musician who refuses to “drop the guitar and sinning ways,” despite his father’s (a pastor) insistence that the blues are a devil’s tool. That tension—between tradition and rebellion, holiness and artistry—runs deep. The twin’s (Stack and Smoke) return to their hometown is a reckoning. “Figured we might as well deal with the devil we know,” one twin says in narration, perfectly summarizing the layered emotional and spiritual undercurrents at play.

There’s also a literal curse at the center of Sinners—money that comes soaked in blood, power traded for souls, and ancestral pacts buried beneath the floorboards of a juke joint bought from a Klan member. The supernatural elements are chilling, but they aren’t there just for fright. They’re allegorical. This is a film about what’s passed down—stories, traditional spiritual discernment, trauma, gifts, and burdens.

When Sammie sings at the new juke joint, it’s more than a performance—it’s an invocation. His music stirs something ancient, channeling both healing and a hint of the fiendish. In a sequence that feels like spiritual possession, Ryan Coogler fuses past and present, collapsing time and culture into a visceral moment that reveals how ancestral rhythms continue to shape and influence today’s norms. It’s in these moments that Sinners truly shines, showing how music connects us across generations and geographies, becoming both a vessel for healing and a conduit for darkness.

A standout early scene, to me, features a reference to 1 Corinthians 10:13—“No temptation has overtaken you except what is common to mankind. And God is faithful; he will not let you be tempted beyond what you can bear. But when you are tempted, he will also provide a way out so that you can endure it. ”—which highlights the biblical tension Sammie’s father introduces through his disapproval of the secular world. Soon after, we witness Smoke revisiting the resting place of the child he and Wunmi lost. Wunmi mentions that the roots had always worked for him—keeping him protected and prosperous even as he profited from “blood money.” But Smoke questions the faith he once placed in those traditions when he asks why the roots didn’t work to save their baby. This intertwining of religion and spirituality reveals that tradition isn’t necessarily abandoned—it’s being reimagined, challenged, and redefined in the face of loss, survival, and identity.

The film also beautifully addresses the presence of Native history through a subplot involving the Choctaw Indians, who once attempted to kill the vampire haunting the juke joint that Stack and Smoke worked tirelessly to turn into a local treasure. There’s an eerie moment when a Choctaw character warns the wife of a Klansman that “the man” was dangerous—but she doesn’t listen, her ingrained prejudice toward nonwhite people overriding her own self-preservation. As the sun begins to set and nightfall approaches, the Choctaw group departs. One of them solemnly tells the woman, “May God be with you,” fully aware of the danger that would soon arrive. This moment symbolizes a powerful convergence of histories—Black, Native, and white legacies all colliding beneath one roof.

Another scene that lingers in my mind comes at the film’s end, when the Our Father prayer is recited. The lead vampire then says: “Long ago, the men who stole my father’s land used to say those words… and I hated that man. But the words still brought me comfort. They told stories about a God above and a devil below, and a dominion of man over beast. We are earth, and beast, and God, and woman, and man—and we are connected to everything.” That quote, to me, encapsulates the essence of Sinners. It’s a story about connection—between people, past and present, pain and power. Through a fluid mix of spiritual horror, historical reckoning, ancestral folklore, and the soul of music, Coogler has created something we’ve never quite seen before in modern Black cinema.

Last but not least, one of the most powerful motifs in the film comes near the end, as the vampires repeatedly ask to be let into the juke joint. This recurring question carries deep symbolic weight: the idea that darkness cannot enter unless invited. It presents a larger spiritual question—will you invite in what’s destructive, or will you recognize it and choose to shut it out? That moment underscores the film’s central message: we all have a choice in the forces we allow to shape our lives.

Ultimately, Sinners is not just a film to be watched; it’s a film to be felt. It’s a reminder that the music of our past doesn’t just echo—it summons. Whether you interpret those echoes as healing spirits or haunting demons is up to you.

#SinnersMovie

#RyanCoogler

#MichaelBJordan

#BlackCinema

#GenreFluidFilm

#IshanaePollard

#BlackFilmmakers

#BlackStorytelling

#Afrofuturism

#AncestralRoots

#HuemanWriters

#VoicesUnleashed

#MusicAndSpirit

#FilmAnalysis

#BlackVoicesInFilm